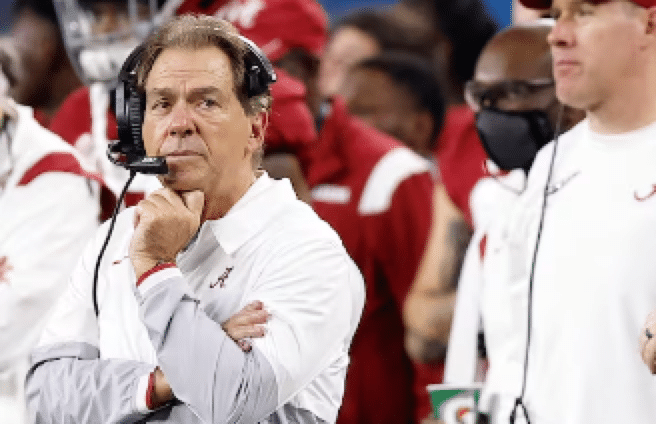

Nick Saban had finished his lengthy press conference with the media at the 2010 SEC Spring Meetings in Sandestin, Fla.

That would be the only chance to get comments from Alabama’s coach.

But I pulled Saban aside and asked if I could get a one-on-one to talk about Tennessee hiring Derek Dooley, since Saban had hired Dooley from SMU to join the LSU staff in the early 1990s.

Saban agreed. And what he said was intriguing.

He said, and I’m paraphrasing, that Dooley was a smart, energetic assistant, eager to learn, and someone Saban could mold into coaching the way Saban wanted him to. Saban said he didn’t want to hire a former head coach because those guys had their own ideas about how to run a program.

Shortly thereafter, Saban hired a plethora of former head coaches, from Bill O’Brien to Lane Kiffin to Steve Sarkisian to Kevin Steele to Mike Locksley to Butch Jones (as an analyst) to Major Applewhite (analyst) and to Dooley (analyst), among others.

It was an about-face change in philosophy.

Saban decided it was better to get fresh ideas and eyes from coaches who had been in his shoes, who had been in the trenches, who had run programs, who had to make tough decisions.

Saban had won by grooming assistants. He also won by hiring former head coaches.

It showed a willingness to adapt.

Saban became known as the rehabilitator of fired coaches.

But the underlying message was Saban was changing with the times.

He once criticized up-tempo offenses, then he ran one.

He once relied on running the football and playing defense. Then he lit up the scoreboard.

He admitted in recent years that you don’t win a championship with just defense. You had to be able to score.

The game had changed, and Saban changed with it.

That’s what made Saban, in my opinion, the greatest coach in the history of college football.

It’s also what made Bear Bryant, in my opinion, the second-greatest coach in college football history.

Saban won national championships at two schools: Alabama and LSU. Bryant won at Maryland, Kentucky, Texas A&M and Alabama.

Each proved they weren’t a one-trick pony, like Joe Paterno or Tom Osborne. Not that Paterno and Osborne weren’t elite coaches. But to win at a high level at different schools shines the resume.

I remember another encounter with Saban at the SEC Spring Meetings.

It was the early 2000s. Saban was coaching at LSU. He had told me he would grant me an interview.

But when the football coaches broke from their meetings, Saban ducked away to an elevator.

Trusting Saban was a man of his word, I did something I wouldn’t dare do today.

I called the front desk at the Sandestin Hilton and asked them to transfer me to Saban’s room.

Saban answered.

I identified myself and told him I was hoping to get an interview – and that I was sorry I missed him when he broke from his meeting.

“Where are you?” he asked.

“I’m by the elevators in the basement, the one you got on to go to your room,” I said.

“I’ll be there in a few minutes,” he said.

True to his word, Saban came back down to the basement elevator. I conducted about an 8-minute one-on-one interview.

Saban grimaced during the interview, like he was getting a root canal. He probably thought of me as a dentist. But he gave straight-forward, insightful and poignant answers.

I appreciated what Saban did that day.

I also appreciated him as a brilliant coach.

He restored LSU to greatness and won a national championship.

He restored Alabama to greatness and won six national championships – and had 17 consecutive 10-win seasons.

I wasn’t shocked at Saban’s retirement. A source who knew Saban and his wife, Terry, told me six years ago that Saban would coach six more years and retire at age 72.

I was relating that story to a friend of mine Tuesday afternoon.

That friend texted me late Wednesday afternoon and said: “You called it.”

I didn’t really call it. I just said don’t be surprised if Saban retires – based on my source from years ago.

While criticized at times for his opinions on the up-tempo offense or the transfer portal or Name, Image and Likeness, Saban, I felt, always had an eye for what he felt was best for college football.

He adapted. And he won. And he won the respect of those that coached for and against him.

He also won the respect of a journalist who appreciated him leaving his comfortable room in Sandestin, matriculating to a basement elevator and doing an interview.

He kept his word.